When I used to ask students what a poem is, I would get answers like “a painting in words,” or “a medium for self-expression,” or “a song that rhymes and displays beauty.” None of these answers ever really satisfied me, or them, and so for a while I stopped asking the question.

Then one time, I requested that my students bring in to class something that had a personal meaning to them. With their objects on their desks, I gave them three prompts: first, to write a paragraph about why they brought in the item; second, to write a paragraph describing the item empirically, as a scientist might; and third, to write a paragraph in the first person from the point of view of the item. The first two were warm-ups. Above the third paragraph I told them to write “Poem.”

Here is what one student wrote:

Poem

I might look weird or terrifying, but really I’m a device that helps people breathe. Under normal circumstances nobody needs me. I mean, I’m only used for emergencies and even then only for a limited time. If you’re lucky, you’ll never have to use me. Then again, I can see some future time when everybody will have to carry me around.

The item he had brought to class? A gas mask. The point of this exercise wasn’t only to illustrate the malleability of language or the playfulness of writing, but to present the idea that a poem is a strange thing that operates as nothing else in the world does.

I suppose most of us have known poems are strange ever since we were infants being put to bed with lullabies like “Rock-A-Bye Baby,” or were children being taught prayers that begin “Our Father, who art in Heaven …” The questions soon arose: What idiot put that cradle in a tree? And what’s art got to do with my Daddy-God? But this kind of strangeness we got used to. And later, at some point in school, we asked or were made to ask again: What is a poem?

For example, in high school, my English teacher handed me Matthew Arnold’s “Dover Beach” and said I had to write an essay about what it meant. I couldn’t make heads or tails out of the assignment, and the poem became the object of my hatred. The poem seemed willfully not to make sense. I soon found every poem to be an irritation, a blotch of words, a ludicrous puzzle that got in the way of true understanding as well as true feeling.

Unless you are a poet or a writer, it’s likely that poems have apprehended you less and less as the years have passed. Occasionally, in a magazine or online you see one—with its ragged right edge and arbitrary-looking line breaks—and it announces itself by what it is not: prose that runs continuously from the left to the right margins of the page. A poem practically dares you not just to look but to read: I am different. I am special. I am other. Ignore me at your peril.

And so you read it and too often become disappointed by its blandness, how it can be paraphrased with an easy moral, such as “this too shall pass” or “getting old sucks”—how essentially it’s no different in content than most of the prose around it. Or, you become disappointed because the poem baffles initial comprehension. It’s inaccessible in its fragmented syntax and grammar, or obscure in its allusions. Nevertheless, you pat yourself on the back just for the trying.

How many of us believe poetry is useless? How many of us don’t even care to ask the question, “Is poetry useless?”

Comparatively, a poem moves a reader, physically or emotionally, very rarely. Other media are much better at bringing us to tears—television, the movies. And if we want the news, we read an article online or glean our Twitter feed. If we want something between tears and the news, we just stare at our children when they ask a question that sounds more like a statement: “Why do grown-ups drink so much beer?”

But seriously, isn’t a poem a home for deep feelings, stunning images, beautiful lyricism, tender reflections, and/or biting wit? I suppose so. But, again, other arts or technologies seem better at those jobs—novels offer us real or imaginary worlds to explore or escape to, tweets offer us poignant epigrams, painting and design offer us eye candy, and music—well, face it, poetry has never been able to compete with that sublime combo of lyrics, instruments, and melody.

There is at least one kind of utility that a poem can embody: ambiguity. Ambiguity is not what school or society wants to instill. You don’t want an ambiguous answer as to which side of the road you should drive on, or whether or not pilots should put down the flaps before take-off. That said, day-to-day living—unlike sentence-to-sentence reading—is filled with ambiguity: Does she love me enough to marry? Should I fuck him one more time before I dump him?

But such observations still don’t tell us much about what a poem really is. Try crowd-sourcing for an answer. If you search Wikipedia for “poem,” it redirects to “poetry”: “a form of literary art which uses aesthetic and rhythmic qualities of language—such as phonoaesthetics, sound symbolism, etc.” Fine English-professor speak, but it belies the origins of the word. “Poem” comes from the Greek poíēma, meaning a “thing made,” and a poet is defined in ancient terms as “a maker of things.” So if a poem is a thing made, what kind of thing is it?

I’ve heard other poets define poems in organic terms: wild animals—natural, untamable, unpredictable, raw. But the metaphor quickly falls apart. Such animals live on their own, utterly unconcerned with the names humans put upon them. In inorganic terms, the poet William Carlos Williams called poems “little machines,” as he treated them as mechanical, human-engineered, and precise. But here too, the metaphor breaks down. A worn-out part on an automobile can be switched out with a nearly identical part and run as it did before. In a poem, a word exchanged for another word (even a close synonym) can alter the entire functioning of the poem.

The most productive thing about trying to define a poem through comparison—to an animal, a machine, or whatever else—is not in the comparison itself but in the arguing over it. Whether or not you view a poem as a machine or a wild animal, it can change the machine or wild animal of your mind. A poem helps the mind play with its well-trod patterns of thought, and can even help reroute those patterns by making us see the familiar anew.

An example: the sun. It can be dictionary-defined as “that luminous celestial body around which the earth and other planets revolve.” But it can also be described as a 4-year-old intuits while staring out the car window on a long winter’s drive: “Mom, isn’t the sun just a kind of space heater?” Another example: honey. According to the dictionary, it’s “a sweet, sticky yellowish-brown fluid made by bees from the nectar they collect from flowers.” According to mothers everywhere, it’s “bee spit that can kill an infant.”

The poem as mental object is no difficult reach, especially if we consider the extent to which pop-song lyrics can literally get stuck, as the neuroscientists tell us, in the form of “earworms” in the synapses of the brain. The intermingling of words and melody has a historied potency going back to schoolyard rhymes that call attention to metalanguage: “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words can never hurt me.” That line itself can hurt, paradoxically, as it perhaps invokes the memory of being called hideous names, whether personalized (Yakich jock-itch) or generalized (camel-jockey).

But when are words most like sticks and stones?

Consider a poem lurking in the pages of The New Yorker. There it is staring you in the face: Do you read it as well as it reads you? In terms of ink on paper, it does nothing more than the prose around it, but in terms of apprehension, it draws in your eye and places the poem in a rarefied position and a totally ignorable one all at once. Oh, look, it’s a precious little chit of words! What a waste of my time!

But there’s also all that white space surrounding it. How much did that cost? The magazine gave up valuable space to print the poem instead of printing a longer article or an advertisement. Nobody bought the copy of The New Yorker for the poem, except perhaps for the poet who wrote it. A poem is a text—a product of writing and rewriting—but unlike articles, stories, or novels, it never really becomes a thing made in order to become a commodity.

A new novel, a memoir, or even a short-story collection has the potential for earning big bucks. Of course, this potential is often not realized, but a new book of poems that yields its author more than a thousand-dollar advance is exceedingly rare. Publicists at publishing houses, even the largest ones, dutifully write press releases and send out review copies of poetry collections, but none will tell you that they expect a collection to sell enough copies to break even with the costs of printing it. Like no other book, a book of poems presents itself not as a thing for the marketplace but as a thing for its own sake.

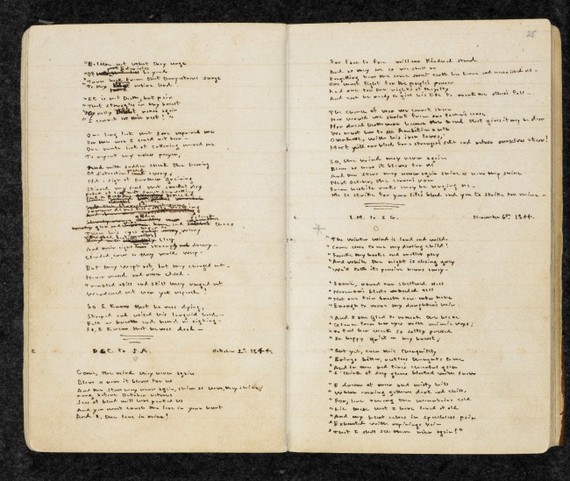

The epitome of such “sake-ness” are poems that put their “made-ness” right in your face. Variously called visual poems, concrete poems, shape poems, or calligrammes, George Herbert’s “Easter Wings” is a canonical example from the 17th century:

The poem’s wings, of birds or angels, coincide or illustrate the textual content: the speaker’s desire to reach skyward toward the Lord. The visual form provides what we might call a little bonus or lagniappe in meaning, and it also makes us notice the poem as more than a raggedy blotch—the blotch itself is meaning.

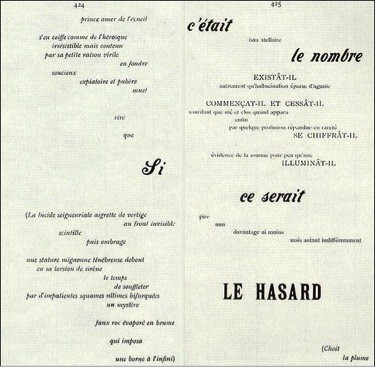

In the 19th century, the French poet Stéphane Mallarmé pushed this page-as-canvas idea even further in Un Coup de Dés (“A Throw of the Dice”). His book-length poem not only manipulates black type, font styles, and white space, but also it exploits the boundaries of the page itself, including the gutter—the seam in the middle of a book—which serves as the alley in which the “dice” (i.e., words) are thrown.

Because the poem allows the reader to make multiple connections between phrases and lines—reading across, down, in combination, or according to specific fonts—some scholars view Un Coup de Dés as a precursor to hypertext. As a reader, you have a certain amount of “freedom” in navigating the poem. The caveat is that freedom often requires more work, more self-motivation, and a certain degree of confusion.

Which brings us back to poetry’s contemporary predicament: a poem that is so strange, so other, is also a poem many feel they might as well ignore. Here’s a poem from the 1960s by Aram Saroyan:

lighght

Yes, that’s the whole poem. I know, it seems asinine. When I wrote it on the board and asked my students to examine it, one said, “How do you even read it aloud?” When we tried, we began to understand the intent of the poem. The word “light” seems to be implied, but what’s with the apparent typo? After a long silence, another student said, “That’s the point—in the ordinary word ‘light’ we don’t pronounce the ‘gh’—the ‘gh’ is silent, and the double ‘gh’ makes us realize that even more.” The poem calls attention to the system of language itself—the stuff of letters in combination—and the relationship between sound and sense. The familiar—a plain word such as “light”—has been made new if only for a brief moment. In Saroyan’s own words: “[T]he crux of the poem is to try and make the ineffable, which is light—which we only know about because it illuminates something else — into a thing.”

When we come across a poem—any poem—our first assumption should not be to prejudice it as a thing of beauty, but simply as a thing. The linguists and theorists tell us that language is all metaphor in the first place. The word “apple” has no inherent link with that bright-red, edible object on my desk right now. But the intricacies of signifiers and signifieds fade from view after college. Because of its special status—set apart in a magazine or a book, all that white space pressing upon it—a poem still has the ability to surprise, if only for a moment which is outside all the real and virtual, the aural and digital chatter that envelopes it, and us.

One might argue that the page is just a metaphor for all that can’t be put on it, and that a poem is merely a substitution, for better or for worse, for a lived feeling or event. And yet, one Jewish tradition admonishes that parents teach their children to love the Talmud not by reading it to them first, but by having them lick honey from its pages. That would seem, to me, an ideal way to experience both bee spit and poetry.